Jets in Distress

Ten bagger in a world leading aerospace business from a developing country

“The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.”

— Warren Buffett | 2007 Shareholder letter

In a case of supreme irony, Buffet built significant positions in Delta, American, United and Southwest airlines starting in 2016, but then had to turn around and sell everything at the peak of the COVID fears in Apr/May 2020. To be fair, it was a black swan event, and he expected the same dynamics of consolidation and rationalization as in railroads that had led him to buy BNSF.

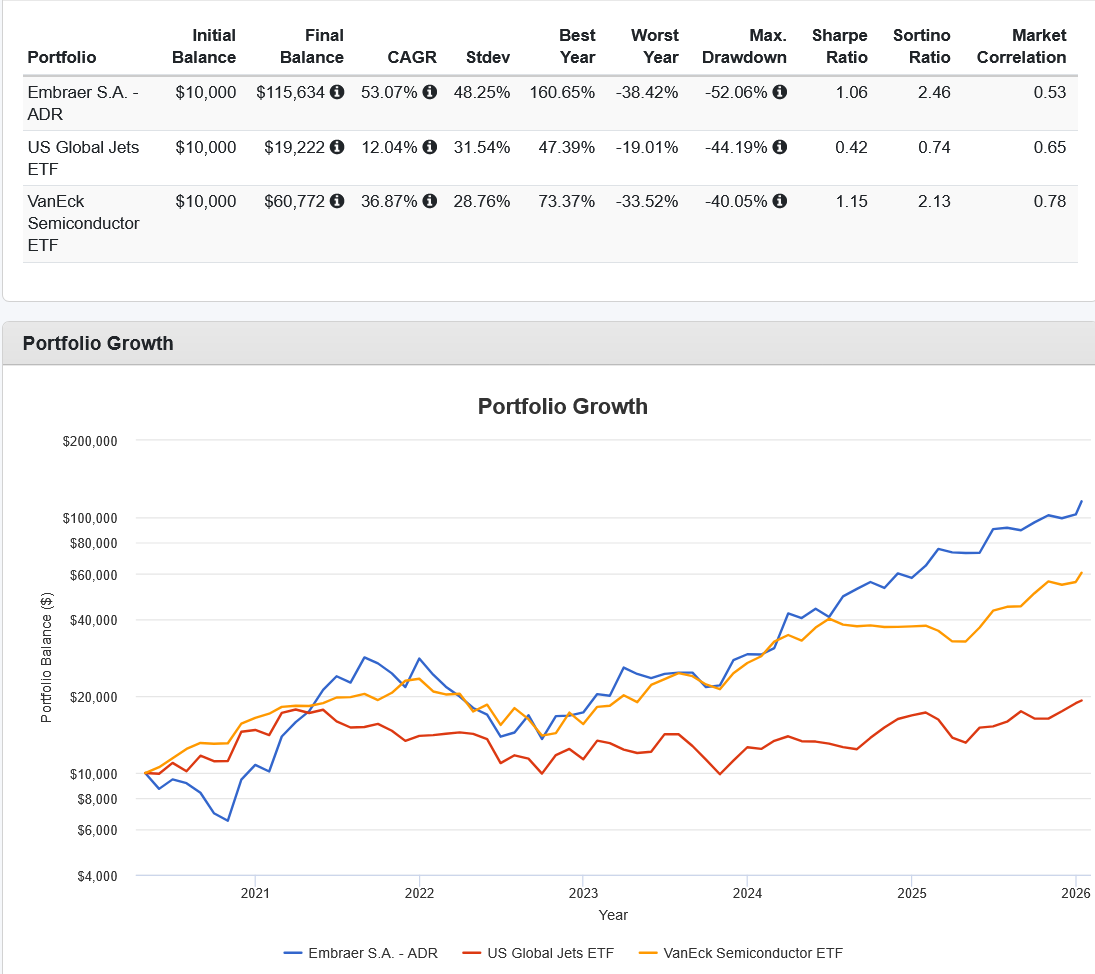

But this story is not quite about that. It’s about a different business that Buffett surely was aware of but did not and likely could not benefit from its ten bagger returns since. Just to get a sense of the magnitude, a 10 bagger since May 2020 would be about double the return of a semiconductor fund (like SMH/SOXX/FSELX)! That’s assuming you somehow had the perfect foresight to predict the semiconductor demand during COVID and the subsequent AI boom. Never underestimate the power of a rebound in an irrationally beaten-up business that has enduring value. Opportunity cost naysayers don’t seem to get that. More on the numbers later.

A note of thanks

First, a thank you to all the new readers. Genuinely surprised at the level of interest. I'm writing mainly to share, clarify my thoughts and hopefully inspire/motivate others who might have similar inclinations. I have many different topics I want to write about in finance, investing and semiconductors. Hopefully I will figure out over time what interests readers the most and try my best to meet that. But I shall also write about things that interest me.

For now, I will continue on the theme of opportunities that informed individual investors with an interest in investing, who put in the effort, do have a shot at doing what Peter Lynch encourages us to do. The markets are not that efficient to arbitrage away such opportunities from small investors. While it’s going to be quite hard to top my first post on Bloom Energy as it was the best example of my investing experience applied to a single name, hopefully you will still find it worthwhile. In fact, I have more to talk about Bloom, but it will have to wait for a future post.

Turnarounds are special

Sometimes you get an insight about a business that you can sit on for years or a decade before you take action at the opportune time. Many of these are typically turnarounds. Everyone thinks of Peter Lynch as a growth or a GARP (growth at a reasonable price) investor, but the reality is that he made just as much money if not more with turnarounds as he himself described (emphasis mine) -

“Some people ascribe my success to my having specialized in growth stocks. But that’s only partly accurate. I never put more than 30–40 percent of my fund’s assets into growth stocks. The rest I spread out among the other categories described in this book. Normally I keep about 10–20 percent or so in the stalwarts, another 10–20 percent or so in the cyclicals, and the rest in the turnarounds.”

I’ve been fascinated by this and have had surprisingly good luck with turnarounds. If you think deeply about it, this is a category that is much harder for the institutional money to play well in due to the limits of size, arbitrage or the lack of ability to stick out your neck too much. An individual could care less about any kind of benchmark and has no one else to answer but his own conviction. On top of that, these stocks are the least correlated to the rest of the market so they can be very good diversifiers for the rest of your plain vanilla diversified or indexed portfolio.

Fateful flight

That was a lot of preambles but bear a bit more. Sometime in the late 2000s, I was flying Air Canada with a short connecting leg. While boarding the plane, which looked like a smaller A320 or B737 from the outside, I noticed that this was a different aircraft that I hadn’t flown or heard of before. I’ve taken a few smaller commuter turboprop or jets before but had not heard of this company called Embraer. As a curious kid growing up, I had the usual fascination with planes, trains and automobiles so I was quite surprised to learn that this was a company from Brazil, and here I was flying in it in a western country. Turns out it was and still is the third most successful commercial aircraft manufacturer in the world.

Quick, how many other world-leading (top 3) non-commodity businesses can you name from a developing country? You might say TSMC, but Taiwan is an advanced economy that’s placed in Emerging Market Indices only due to market/currency access and financial regulation issues. Same goes for South Korea. I doubt it’s easy to find an example like Embraer, but I’d be curious to learn in the comments. Anyway, that led me to do a whole of lot of reading up on Wikipedia and other places about Embraer, its jets and how exactly they managed this remarkable feat. More about that later. At the time it was without any specific investing angle. Just knowledge acquisition, filed away if needed later.

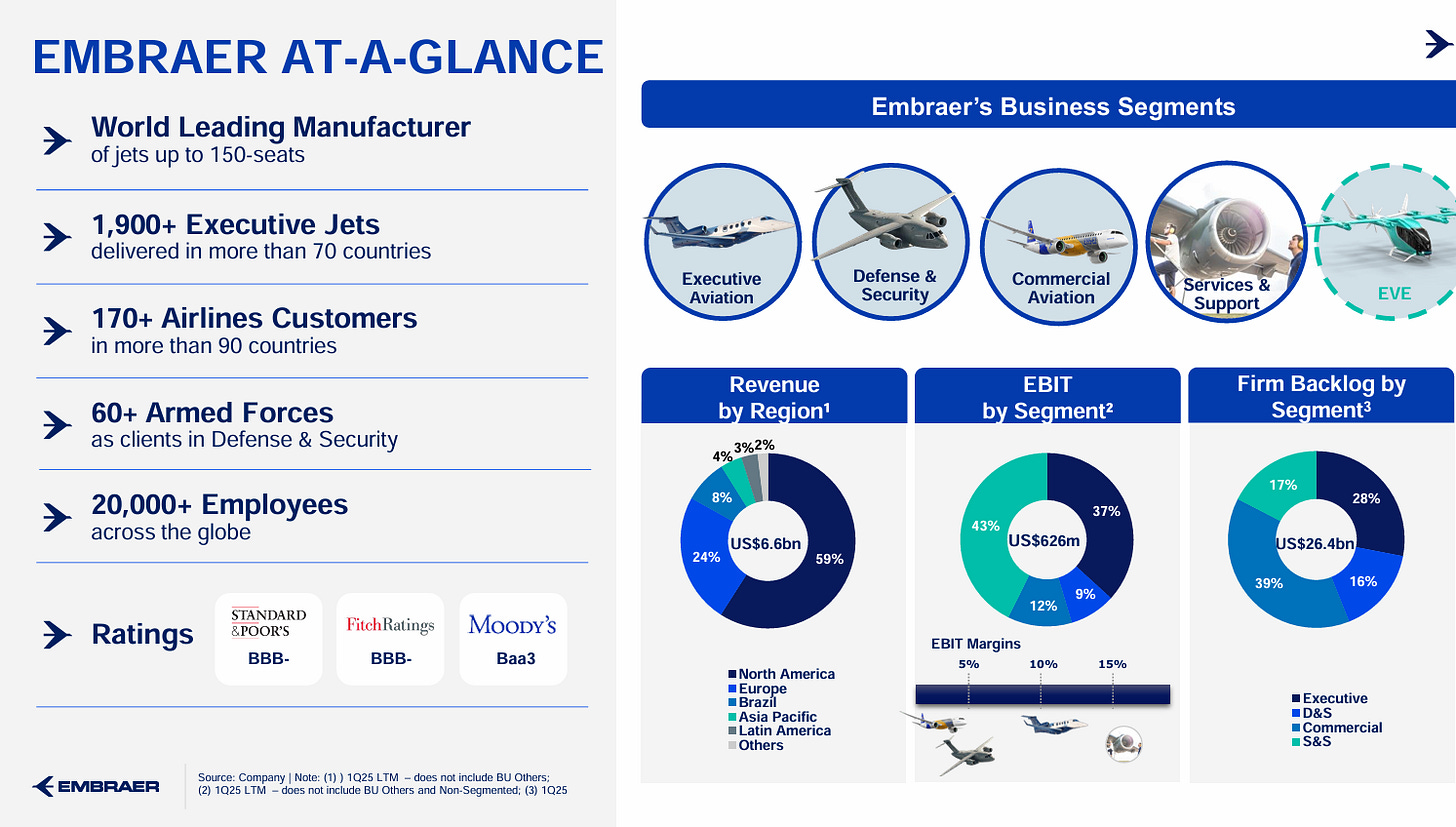

Before we learn more about how Embraer EMBJ 0.00%↑ achieved this astounding feat, a very brief overview of what it does. Embraer is the world leader in smaller (than B737/A320) single aisle jets and regional jets, a leading player in small to mid-size business jets along with a sizeable defense business. See the slide below from Embraer for a quick overview.

Competitive pressures and the COVID shock

While Embraer had a long history with its regional/small narrow-body jets, having a large share of the up to 150 seat market, it was facing a bunch of new competitive pressures with various events set in motion before the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, Canadian company Bombardier which was always an archenemy and nemesis in regional jets with its CRJ family was developing a newer larger C-Series Jet. This was an extremely expensive endeavor from a company that wasn’t as well managed as Embraer. Ultimately, they had to partner with Airbus which later fully took over the C-Series as the A220. In addition, Mitsubishi from Japan (which has an aerospace business) was developing its own regional jet called the SpaceJet for the same market. Bombardier then decided to sell the older CRJ family to Mitsubishi. There were also minor players in the Chinese Comac ARJ21 and the Russian Superjet 100, but these didn’t have much adoption in western countries.

The C-Series partnered with Airbus along with other new competition would have been a major headache for Embraer. The commercial aviation business (in comparison to business jets) is not easy as it typically has low to no margins on aircraft sales which is later made up via service contracts. Therefore, the value of existing relationships with airlines and scale is important. Boeing had been wary as well of the C-Series encroaching on the lower end of B737 sales, so this was the perfect setup for a joint venture deal announced with Embraer in July 2018 for an 80% stake in the commercial aviation regional jets business. This would in theory allow Embraer to concentrate on the more lucrative business jet and defense segment. Finally, another pivotal event was the second fatal crash of the Boeing 737 MAX in March 2019 which led to its worldwide grounding.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Nothing related to these aviation companies would ever be the same again.

“There’s the little-problem-we-didn’t-anticipate kind of turnaround, such as Three Mile Island. This was a minor tragedy perceived to be worse than it was, and in minor tragedy there’s major opportunity. I made a lot of money in General Public Utilities, the owner of Three Mile Island. Anybody could have. You just had to be patient, keep up with the news, and read it with dispassion.”

— Peter Lynch | One Up on Wall Street

COVID certainly looked like a nuclear disaster level event for most transportation businesses when everything came to a screeching hard stop. Boeing was in deep trouble due to the MAX incident and how it was handled. Heavy criticism was levelled at for having lost engineering ethos with bean counters in control. The first casualty was Boeing terminating its deal with Embraer. The market decided to sell Embraer first and ask questions later with the stock dipping into the $5 range and below a billion dollar market cap. The valuation was around 0.2 to 0.3 on a Price/Sales and Price/Book basis.

This was getting to be ridiculous territory for a business that still had all its aircrafts out there to be eventually used again by the airlines/operators. The value of all these jets was the long-term service contract revenue that had to come in when they flew again even if the short term wasn’t clear. It’s not easy to develop a new aircraft, get FAA and EASA approvals and airline sales as even an experienced player like Bombardier found out. The other newcomers had a slimmer chance in my opinion. The market also seemed to forget that the defense business was not going anywhere. The longer-term risk/reward looked good, and I decided to buy some -

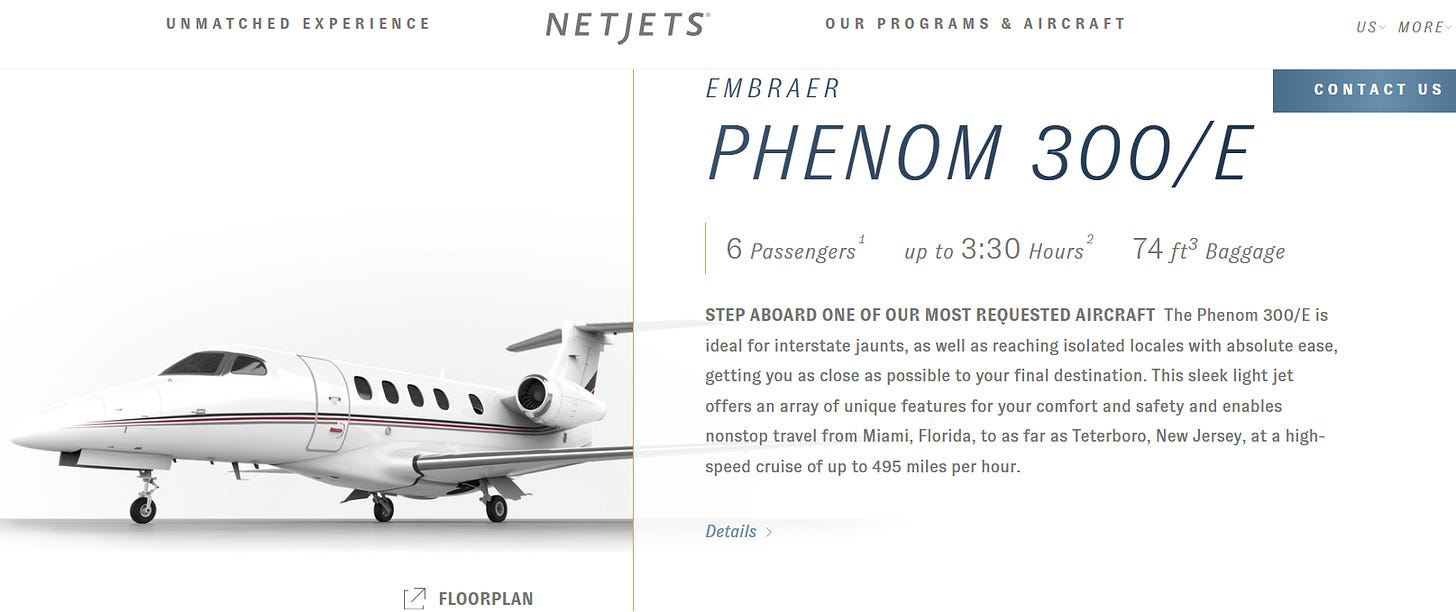

Coming back to Buffet, Berkshire has owned fractional ownership jet operator NetJets since 1998, which is an operator of Embraer’s business jets. In fact, exclusively at the light jet level -

However, with Embraer below a billion dollars market cap, it would have moved the needle very little for a 400 billion dollar market cap Berkshire Hathaway (at the time). In any case Buffett seemed quite cautious during COVID and didn’t seem to do any of his characteristic “buying when others are fearful” except the Japanese trading houses much later in the year. I’m not sure if it had something to do with having a large insurance business. But as I mentioned earlier, this is where small investors can press their advantage.

Some folks were thinking of reprising Buffett with airline stocks even cheaper or cruise operators at the time but those did not do as well. It’s not just a matter of buying anything that is beaten down. Airlines are dime-a-dozen, but businesses like Embraer have barriers to entry like technical knowledge, experience and type certifications etc. Not to mention competitive advantages like switching costs for the airlines.

Turnaround

As Lynch said, you just had to be patient, keep up with the developments and wait for things to get better. In fact, you didn’t have to wait that long. Mitsubishi folded and significantly scaled back its SpaceJet program the same month, then suspended it later in the year to finally terminate it in 2023. Mitsubishi ended the CRJ production as well in Dec 2020 and never revived it. Bombardier sold its A220 stake to Airbus to completely exit commercial jets and focus on business jets. Later geopolitical events mean that the Russians and the Chinese are even less likely to sell their aircrafts into the western market.

This left the Embraer E-175 as the only aircraft for a certain segment of the US regional aircraft market. Mainline airline pilots in the US negotiate something called a scope clause in their contract which restricts the mainlines regional airline network from flying aircraft larger than 76 seats to limit outsourcing competition. The Airbus A220 is too big for this, and Mitsubishi ended production of the only other option the CRJ-700 as mentioned earlier. Note that unlike Southwest, the major legacy airlines have a hub and spoke model where they need regional airlines to feed traffic from smaller cities into the hubs. The A220 will get sales in the larger flag carriers in the rest of the world but the Embraer E/E2 jets are the right size for thinner routes where the A220 is “too much plane”. Not to mention lower price/complexity and existing familiarity for the operators.

But Embraer is not just the commercial E/E2 jets. They have a very good franchise in business jets which naturally had a multi-year upswing starting in 2021 due to the wealthy wanting to avoid bigger airlines during COVID. The defense business has the new KC-390 military transport aircraft which is a phenomenal achievement (beyond the scope of this post, but you if are interested compare with the troubles faced by the much bigger Airbus A400M). Overall revenue started rebounding in 2021 and steadily increased to all-time highs in 2024. All divisions contributed to the margin rebound in 2023-2024 and now are at a decade high with low leverage and investment grade rating. And it shows in the performance since May 2020 -

How Embraer become a world leader

Let’s take a very brief look at my distillation of how Embraer became a world leader in aircraft manufacturing. This is not an easy feat. There have been many developing countries that have tried to develop an industry in a technologically difficult field either with or without explicit state support, but very few have accomplished what Brazil has managed to do.

Aviation heritage

Coming back to the Wright brothers, the Wikipedia entry for the 1903 Flyer (Wright Flyer) says - “first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft”. Note the number of qualifications. If you remove one or some of them then others have a claim. A Brazilian has a legitimate claim to be one of the leading luminaries of this “pioneer era” of aviation. Alberto Santos-Dumont (who lived in Paris at the time) achieved the first powered flight by a non-Wright flyer in 1906 which was also the first to be witnessed in public and filmed (as the Wright brothers tried to operate in secrecy for about 5 years after their first flight). He contributed in many other ways to the knowledge of aeronautics both before this via his hot air balloons and later by making the design of his influential Demoiselle aircraft freely available. It’s a pity that the western world doesn’t seem to recognize him as much.

14-bis replica re-enactment at a military air show in Sao Paulo | Aviões e Músicas (Youtube)

Santos-Dumont later wrote in his letters to the president of Brazil stressing the need to build military airfields for the Army and the Navy. He also pointed out that Brazil was falling behind Europe, the United States and even Argentina and Chile. In a book he argued for the need to train people in aeronautics, and to make the country technologically independent.

We should not underestimate the cultural and psychological background of this. In Brazil, he’s treated as the father of aviation and a national hero. It probably led to the thinking that Brazilians can be at the technological frontier and a small but real cadre of pilots and officers who cared about aviation as a strategic domain. I’m sure it has continued to inspire generations of Brazilians.

Firm institutional foundations to an aerospace cluster

Casimiro Montenegro Filho who was a Brazilian Air Force officer (Air Marshall later) took those ideas and proposed the creation of an aeronautical higher education institution and an R&D center in 1943. This led to the creation of ITA Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica (Aeronautics Institute of Technology) modeled on MIT and led by MIT prof Richard Harbert Smith in 1950. It is Brazil’s top engineering school, producing thousands of aerospace engineers (many of whom work at Embraer).

The R&D center was also established as the Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia Aeroespacial (Department of Science and Aerospace Technology) DCTA in 1953.

I believe this led to a technological cluster that had both the human capital and the national backing to be given time to mature into something globally competitive.

Crawl walk run (with the best)

In 1969 the Brazilian Military Dictatorship established Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica (Brazilian Aeronautics Corporation) which was shortened by the syllabic abbreviation to Embraer. The firm inherited the knowledge and tooling from ITA and DCTA.

Embraer first produced the EMB-110 Bandeirante which was a 15–21 seat turboprop designed for the Brazilian Air Force and regional routes. This was later upgraded to the EMB-120 Brasilia which was a 30-seat pressurized commuter aircraft that hit the US/European regional airline wave in the 1980s. But the key insight is that these were export-oriented from day one, consciously aimed at the global commuter market and had to meet Western certification standards.

Embraer also did licensed production of Piper light aircraft for Latin America and built trainers and light attack aircraft (Tucano) for the Brazilian Air Force and export customers (as Short Tucano for the Royal Air Force), giving them a stable home market and defense-funded R&D.

Privatization and Jet launch

Like most state champions, Embraer almost died when the global environment changed. The end of the Cold War and the Brazilian debt/hyperinflation wrecked its defense budget. Embraer was loss-making and went into Brazil’s privatization program in 1992 and was sold in 1994, with the state keeping only a golden share.

This forced a commercial focus, leaned it out and aligned it with market reality

by greenlighting the ERJ-145 regional jet with 37–50 seats as a stretch of the earlier EMB-120, designed squarely around US/European regional airline needs. By 1996 they sold around 200 ERJ-145s at Farnborough, a huge commercial breakthrough.

This was a clever niche selection and timing. A regional jet no one else loved. US airline deregulation led to the hub-and-spoke networks and the “scope clause” we talked about earlier, so it made regional jets attractive. Mainline carriers wanted outsourced feeder flights, not B737/A320 sized airplanes. Their main rival was Bombardier instead of Boeing/Airbus. Then they did it again in the late 1990s/early 2000s as they read the shift to larger regional jets and launched the E-Jet family (E170/175/190/195, 70–120 seats). In the 2000s they smartly moved into business jets which have much better initial sale economics as its more akin to selling a luxury product.

Another underappreciated reason for Embraer’s success is risk sharing partnerships with major suppliers and the focus internally only on systems integration and final assembly using the best components and subsystems from around the world. They did not try to invent everything themselves and focused on the real value add.

In the end Embraer and Brazil succeeded because inspired by their heritage they built the institutions, people and ecosystem first. Then they started small in a defensible niche that was slowly and continuously improved in an export market competing with the best. Privatization made them focus on niche regional jets. Finally, their focus was always on systems integration.

Conclusion

I hope I have once again shown that there are opportunities individual investors can seize by building their knowledge slowly over time about a specific industry or company and pounce when the right opportunity arises. As Buffet says there are no called strikes in investing. Wait patiently for the fat pitch and swing. And as Lynch says anyone can do it under the right circumstances.

Lastly, I will leave you with a little appreciated statistic. Less than an estimated 20% of the world’s population has ever flown on an airplane.

Disclaimer: None of this meant as advice. I would encourage you to do your own research and invest according to your circumstances.